Abstract

Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis refers to spinal deformity that develops from just before the onset of puberty until the completion of skeletal growth, and the primary goal of treatment is to achieve a well-balanced spine. In the late 1990s, advances in the anatomical understanding of the spine and the development of fixation instruments made posterior pedicle screw insertion feasible, thereby enabling the transmission of powerful corrective forces for deformity correction. Over the subsequent decades, accumulated clinical experience and outcomes have provided a deeper understanding of scoliotic curves and led to the establishment of effective principles for determining the extent of spinal fusion. However, these treatment principles are based on the unique biomechanics and procedural characteristics of scoliosis correction surgery, which can make them difficult to understand without sufficient explanation. In this review, we aim to describe these established treatment principles and surgical processes in detail using schematic illustrations and images. Although these principles will continue to undergo new challenges and validation over time, they will remain a meaningful reference point for those exploring alternative strategies.

-

Keywords: Classification in AIS, Fusion levels in AIS, Pedicle screw instrumentation, Deformity correction

Abstract

청소년기형 척추 측만증이란 사춘기가 시작되기 직전부터 골격 성장이 완료되는 시기에 나타나는 척추 측만증을 의미하며 치료의 목적은 균형된 척추를 만드는 것입니다. 1990년대 말, 척추의 해부학적인 이해와 고정 기구의 발달로 후방 척추경 나사 삽입이 가능해졌고, 이를 통하여 강한 변형 교정력을 전달할 수 있게 했습니다. 이후 수십년간 축적된 임상경험과 결과들은 만곡에 대한 깊은 이해를 제공했고 유합 범위의 결정에 유효한 원칙이 정립되었습니다. 다만, 이러한 치료 원칙들은 측만증 교정 수술의 특수한 기전과 과정에 기반하고 있어, 충분한 설명 없이 바로 이해하기에는 어려운 부분이 존재합니다. 본 리뷰는 이러한 정립된 치료원칙과 과정을 도해와 이미지를 이용하여 상세히 설명하고자 합니다. 정립된 치료원칙도 시간에 따라 새로운 도전과 검증을 거치겠지만, 대안을 탐색하는 이들에게는 지속적으로 의미 있는 기준점이 될 것입니다.

-

색인 단어: 청소년 특발성 척추측만증의 분류, 청소년 특발성 척추측만증에서의 유합 범위 결정, 척추경 나사 고정술, 변형 교정

Introduction

Advances in the understanding of spinal anatomy and in technology led to the development of pedicle screw fixation.

1) Based on the superior fixation strength of spinal screws, strong corrective forces can be effectively transmitted to the spine, and the rod-derotation technique enables realignment of scoliotic deformities into a normal thoracic kyphotic profile.

2) Over subsequent decades, accumulated clinical experience and outcomes have enabled prediction of various complications, and at present, relatively wellestablished treatment principles are in place.

3,4)

Accurate application of treatment principles requires precise assessment of the spinal curve, which is achieved through appropriate classification and identification of the index vertebrae.

5-7) Subsequently, in patients who meet the indications for surgery, the surgical goal is to achieve a wellbalanced spine. During the surgical planning process, selection of the appropriate fusion levels is of critical importance. Additionally, correction of shoulder imbalance should be addressed, and efforts should be made to preserve the distal mobile segments.

7,8)

In surgery for patients with spinal deformity, precise pedicle screw placement is of paramount importance. Inaccurate screw insertion can lead to dural tears, pedicle fractures, pleural effusion, pneumothorax in severe cases, loss of correction, and even neurovascular injury.

9) The process of connecting metal rods to the inserted screws and transmitting corrective forces to address the deformity is a fundamental and distinctive step in scoliosis correction surgery.

2)

A thorough understanding of curve is essential to select appropriate surgical levels and to perform surgery with precision in accordance with these principles. This review aims to provide a detailed explanation of these treatment principles and their practical application for broader surgeons. Using prepared schematic diagrams and images, we aim to provide a detailed explanation of curve classification, selection of the proximal and distal fusion levels, accurate pedicle screw insertion, and deformity correction using adjunctive techniques, including rod-derotation.

1. Classification of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis

One of the most representative classification systems is the King–Moe classification

5) proposed in 1983, which is specifically focused on thoracic curve patterns (

Fig. 1), However, because it lacks consideration of curve flexibility, it is excellent as a morphological classification but is less suitable for detailed assessment of the curve.

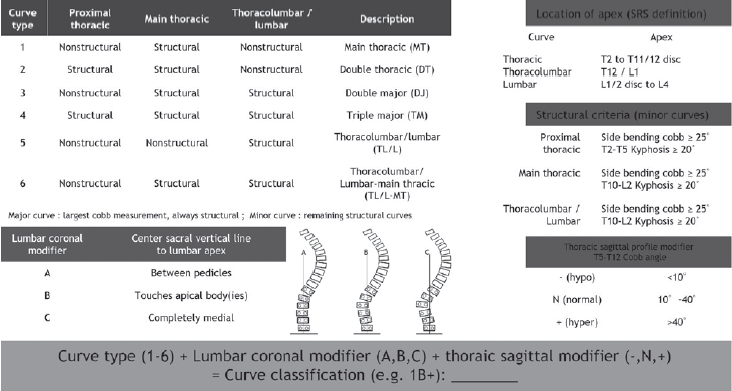

The Lenke classification

6) has the advantage of incorporating structural curve assessment as well as lumbar deformity and sagittal alignment; however, the system itself is excessively complex, comprising as many as 42 subtypes, and the lumbar and sagittal modifiers do not exert a decisive influence on determining the actual fusion levels (

Fig. 2). Although surgeons may use classification systems as a guide when determining the surgical extent, it is more important to focus not on the classification itself but on understanding the unique characteristics of the individual patient’s curve in comparison with others, and to define the appropriate surgical range through an appreciation of its underlying nature.

10)

2. Proximal fusion level selection.

With respect to selection of the proximal fusion level, postoperative shoulder imbalance remains one of the most controversial issues and represents a complex, multifactorial problem characterized by a discrepancy between radiographic findings and cosmetic appearance. Nevertheless, correction of a structural proximal thoracic curve has been strongly emphasized. Failure to address a structural proximal thoracic curve while correcting only the main thoracic curve may result in unacceptable postoperative shoulder imbalance (

Fig. 3).

4,11)

When correcting the proximal thoracic curve, selection of T2 rather than T3 as the uppermost instrumented vertebra was superior in terms of correction of T1 tilt and the proximal thoracic curve, as well as facilitating more natural improvement in shoulder balance.

8)

Additionally, in cases with a structural proximal thoracic curve, pedicle screw insertion at T3 or T4 is not always safe because of the extremely narrow pedicle width on the con-cave side. In contrast, T2 has a sufficiently wide pedicle and allows safe placement using standard pedicle screw insertion techniques (

Fig. 4).

4,12)

3. Distal fusion level selection.

Just as shoulder imbalance should be taken into account when determining the proximal fusion level, the “adding-on” phenomenon must be considered when selecting the distal fusion level. The adding-on phenomenon is characterized by a progressive loss of correction below the lowest instrumented vertebra, caused by lumbar vertebral deviation or an increase in disc angulation(

Fig. 5).

3,4) At the distal end of the thoracic curve, three characteristic index vertebrae should be identified, among which the neutral vertebra is the most critical reference point. The neutral vertebra is defined as the vertebra that shows bilateral pedicle symmetry on radiographs, indicating the absence of axial rotation. Fusion should ideally be extended to the neutral vertebra, or at least to one level above it (

Fig. 6).

4,6) If the fusion is extended to a level shorter than this, the adding-on phenomenon frequently occurs, generally resulting in unsatisfactory outcomes (

Fig. 5).

3,4)

4. Exacting screw insertion technique

Pedicle screw insertion using the free-hand technique is performed without additional guidance or adjunctive assistance. This method relies on the surgeon’s subjective tactile feedback and knowledge of normal spinal anatomy; however, spine surgeons may encounter limitations when inserting screws at the apical region of severely rotated deformities. A high incidence of cortical perforation has also been reported, suggesting that there may be limitations in achieving accurate pedicle screw placement without adjunctive assistance in pedicles with deformity.

13) Therefore, this technique may be applicable in non-deformed spines, but its effectiveness in deformed spines can reasonably be questioned.

4)

Pedicle screw insertion targeting the presumed medial margin on true posteroanterior C-arm imaging is an accurate, safe, and practical technique even in very small pedicles. To apply this technique, preoperative review of 1-mm reconstructed axial CT images along the pedicle of each vertebra is first performed to determine the appropriate screw size and pedicle diameter for each level. This method may be a particularly useful option for less-experienced spine surgeons when inserting screws into the small pedicles of patients with scoliosis (

Fig. 7).

4,14,15)

5. Rod derotation, compression and distraction maneuvers

After screw insertion, a rod contoured with a slight exaggeration of the normal sagittal profile is inserted to span the segments to be corrected. When the corrective rod is rotated 90 degrees using clamps or a rod holder, the scoliotic deformity is converted into thoracic kyphosis in the thoracic spine and lumbar lordosis in the lumbar spine, thereby restoring sagittal alignment; this maneuver is referred to as rod derotation.

16) However, if the rod is extended into the proximal thoracic spine, rod derotation may result in the creation of proximal thoracic lordosis, leading to inappropriate correction. In such cases, to achieve thoracic kyphosis, the proximal thoracic rod should be rotated in the direction opposite to that of the main curve. Separate correction of the proximal thoracic curve can then be connected using a rod connector (

Fig. 8).

4)

After separate derotation, convex-side compression was applied to the proximal thoracic curve, while concave-side distraction was performed for the main thoracic curve. This compression–distraction strategy is a reliable method for correcting both curves while achieving acceptable postoperative thoracic kyphosis and shoulder balance (

Fig. 9).

4,8)

Conclusions

Treatment of idiopathic scoliosis has a long tradition. However, no perfect classification system exists, and treatment principles and surgical techniques continue to evolve. Nevertheless, at the present time, the best way to provide optimal care for the patient in front of us is to study and understand the various curve patterns and to adhere to the most appropriate treatment principles. Even when contemporary principles are followed in individual clinical practice, technical and societal changes will inevitably occur, and as these principles are applied and refined by many, new, eraappropriate treatment paradigms will emerge. This process should be pursued collectively, with integrity and a commitment to building upon shared experience.

Fig. 1.King and moe classsification: curve patterns.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 3.

Post-operative shoulder imbalance.

If the main thoracic curve is overcorrected without addressing the structural proximal thoracic curve, an undesirable postoperative shoulder imbalance may occur.

Fig. 4.Axial CT scan image of Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis, demonstrating that the pedicle at T2 is relatively wide compared with those at T3 and T4. (A) The pedicle width on the concave side T2 was also measured to be sufficiently wide at 2.8 mm. (B, C) In contrast, the concave-side pedicles at T3 and T4 were measured to be extremely narrow, at 0.6 mm and 0.4 mm, respectively.

Fig. 5.Adding-on occurs when fusion does not extend to the neutral vertebra (NV). Both (A) and (C) presented with a King type 3 curve with the neutral vertebra at T12. Case (C), in which T12 was selected as the LIV, was treated appropriately like case (D) without any adding-on. In contrast, case (A) did not adhere to the appropriate treatment principles, and, as illustrated in case (B) subsequent lumbar vertebral deviation and disc angulation developed, consistent with the adding-on phenomenon.

Fig. 6.

Three distinctive index vertebrae at the distal end of the curve.

Neutral Vertebra (NV): The vertebra showing the least or no axial rotation, typically with symmetrical pedicles. End Vertebra (EV): The most tilted vertebrae at the upper and lower ends of the curve used to measure the Cobb angle. Stable Vertebra (SV): The most caudal vertebra bisected or nearly bisected by the C7 plumb line or CSVL, indicating coronal balance.

Fig. 7.pedicle screw placement method by targeting presumed medial margin in a true PA C-arm image. The sequence illustrates, in order, the patient positioned in the prone posture, the relationship between the rotated vertebra and the C-arm, a three-dimensional model of the vertebra, and the resulting C-arm images obtained. (A) After posterior exposure of the spine, C-arm fluoroscope is positioned at the target vertebra to obtain a PA image. (B) The C-arm is gradually rotated until a true PA view of the rotated vertebral body is acquired and both pedicles are symmetrically visualized en face. (C) An imaginary pedicle outline is presumed with the elliptical or linear shadow being the medial margin of the pedicle. The entry point of a screw is made at 10-o’clock position in the presumed pedicle outline.

Fig. 8.The necessity of separate-rod derotation (A) Absence of separate derotation resulted in the development of thoracic lordosis following rod derotation. (B) Separate derotation using a rod connector allowed successful correction and restoration of thoracic kyphosis.

Fig. 9.Combination of convex compression for the proximal thoracic curve and concave distraction for the main thoracic curve after separate-rod derotation.

References

- 1. Suk SI, Lee CK, Kim WJ, Chung YJ, Park YB. Segmental pedicle screw fixation in the treatment of thoracic idiopathic scoliosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1995;20(12):1399-405.

- 2. Suk SI, Kim WJ, Kim JH, Lee SM. Restoration of thoracic kyphosis in the hypokyphotic spine: a comparison between multiple-hook and segmental pedicle screw fixation in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. J Spinal Disord. 1999;12(6):489-95.

- 3. Lee CS, Hwang CJ, Lee DH, Cho JH. Five major controversial issues about fusion level selection in corrective surgery for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: a narrative review. Spine J. 2017;17(7):1033-44.

- 4. Kim HS, Gwak HW, Kang HW, Lee CS. Corrective Surgery for Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, Rosemont, IL. Orthopaedic Video Theater, March 1, 2025.

- 5. King HA, Moe JH, Bradford DS, Winter RB. The selection of fusion levels in thoracic idiopathic scoliosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1983;65:1302-13.

- 6. Lenke LG, Betz RR, Harms J, Bridwell KH, Clements DH, Lowe TG, Blanke K. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: a new classification to determine extent of spinal arthrodesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83(8):1169-81.

- 7. Suk SI, Lee SM, Chung ER, Kim JH, Kim WJ, Sohn HM. Determination of distal fusion level with segmental pedicle screw fixation in single thoracic idiopathic scoliosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2003;28(5):484-91.

- 8. Lee CS, Park S, Lee DH, et al. Is the Combination of Convex Compression for the Proximal Thoracic Curve and Concave Distraction for the Main Thoracic Curve Using Separate-rod Derotation Effective for Correcting Shoulder Balance and Thoracic Kyphosis? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2021;479(6):1347-56.

- 9. Di Silvestre M, Parisini P, Lolli F, Bakaloudis G. Complications of thoracic pedicle screws in scoliosis treatment. Spine. 2007;32(15):1655-61.

- 10. Lee CK, Koo KH, Ahn JH. Classification of idiopathic scoliosis. J Korean Spine Surg. 2007;14(1):57-66.

- 11. Lee CS, Hwang CJ, Lee DH, Cho JH. Does fusion to T2 compared with T3/T4 lead to improved shoulder balance in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis with a double thoracic curve? J Pediatr Orthop B. 2019;28(1):32-9.

- 12. Lee CS, Cho JH, Hwang CJ, Lee DH, Park JW, Park KB. The Importance of the Pedicle Diameters at the Proximal Thoracic Vertebrae for the Correction of Proximal Thoracic Curve in Asian Patients With Idiopathic Scoliosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2019;44(11):E671-E678.

- 13. Liljenqvist UR, Halm HF, Link TM. Pedicle screw instrumentation of the thoracic spine in idiopathic scoliosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1997;22(19):2239-45.

- 14. Lee CS, Kim MJ, Ahn YJ, Kim YT, Jeong KI, Lee DH. Thoracic pedicle screw insertion in scoliosis using posteroanterior C-arm rotation method. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2007;20(1):66-71.

- 15. Lee CS, Park SA, Hwang CJ, et al. A novel method of screw placement for extremely small thoracic pedicles in scoliosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2011;36(16):E1112-E6.

- 16. Suk SI, Kim JH, Kim SS, Lim DJ. Pedicle screw instrumentation in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS). Eur Spine J. 2012;21(1):13-22.

Figure & Data

Citations

Citations to this article as recorded by